MARK WAIL’S UNKNOWN AND KNOWN ILHOM THEATER.

Mark Wail‚Äôs unknown and known Ilkhom Theater. The experience of creating a theater from the ‚Äúzero‚Äù: history, legendary performances, director’s notes.

Fragments from the book

In the mid-1970s the crisis of the system co-occurred with the peak of a diverse, sometimes painful search in the intellectual and spiritual life of our society.

Ilkhom appeared exactly when no one believed in anything, when 10 years before the Gorbachev’s era it was impossible to imagine how history would flow.

Ilkhom was born when the ideologists of the system completely trafficked in lies, and the new generation no longer wanted to put up with it.

The history of Ilkhom is also my personal history. The history of a young man who, simply because of his youth and the inherent independence of views, did not find himself in any of the public institutions and, contrary to common sense (because few people managed to regain their independence in the Soviet system), started his own business, his Theater, which, as it would become clear later, turned out to be formally the first professional theater company independent of state bodies in the USSR.

***

We did almost reckless things, rehearsing plays not reviewed yet by censorship. Under the laws of the Soviet era, we were threatened with a criminal liability for anti-Soviet activity. Colleagues of the older generation attended our performances with horror. We simply did not understand the reason for this fear. And it was this that indicated our difference, born in the relatively warm “Khrushchev’s era”, which saved people from the total fear caused by the Stalinist terror.

We were not a political theater, in our performances there were no calls, protests, which, for instance, the New Left Theater or the Brecht Theater preceding it had abundance of.

Simply unedited life and the living appeared on our stage.

They could be eccentrics, as in the absurd “Fountain Scenes” by Semyon Zlotnikov or absolutely real characters: cynical, pragmatists, who do not believe in love, in family, or in serving the motherland, with the characters of “Duck Hunt” by Alexander Vampilov resembling this. Finally, we simply were free to experiment with form and style in our performances, without declaring adherence to any ideology – and this was enough to make our works perceived as “anti-Soviet performances” at the time when Ilkhom just started. Since their mood, characters and arts media did not fit into accepted stereotypes. Least of all do I want to imagine myself and the pioneers of Ilkhom as heroes. We would express ourselves, but Soviet reality reflected us in its crooked mirror, judged, and imposed its ideology.

***

Sometimes it seems that we have lived several lives. There were too many things.

At the same time, we, yesterday’s ‚ÄúSoviet young avant-garde artists‚Äù (as they tried to classify us), did not have time to look back, as the years passed. 10 years later, after we started, a completely different time came. And then it was quickly replaced by new and significant events for history.

Ilkhom was saved from destruction by the Perestroika. Exactly one year before Gorbachev, we received a written order to stop playing the five titles of our repertoire. Ilkhom was checked by some commissions. They wrote some papers. The KGB collected “written evidence from the public” demanding that the theater be sorted out and closed.

…

Gorbachev’s time turned everything upside down. In a short period of time, the army of former officials was removed from their positions. Society, the media started to speak up. The new officials got repainted on a single day and suddenly began to raise Ilkhom as a flag of the new era. Some awards were poured on me. Without any long bureaucratic presentations, I received the title of Honored Artist, a large apartment (before, I lived with my family in one bedroom flat, and in Soviet times the state controlled the distribution of housing fund). I was invited to teach at the Institute of Arts.

They started to invite Ilkhom to official festivals. Finally, we were allowed to register the theater as an organization: open a bank account, start selling tickets, earn money for ourselves.

Everything began to resemble a Hollywood movie with a happy ending. Dozens of theaters around us rushed to stage the once forbidden plays: “Dear Elena Sergeyevna” by L. Razumovskaya, “Farewell to the ravine” (“Dogs”) by K. Sergeenko, plays by A. Chervinsky, S. Zlotnikov, Sh. Bashbekov, etc. which were staged by Ilkhom long before them, paying in full for obstinacy.

At that time, we really felt that we were ahead of time.

At that time, we really felt that we were ahead of time. At once, we lost interest in plays with words and for a long time plunged into experimental work on no-words plays: a visual theater-metaphor, a theater of clowning. We made several television versions of our work.

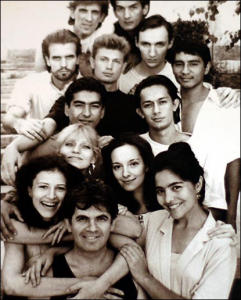

The face and composition of the theater began to change. The life of the actually new Ilkhom began. The actors who played the performances “Ragtime for Clowns”, “Clomadeus”, “and Parsley” brought new energy to the theater and a sense of new perestroika time Theater.

At the same time, the Ilkhom conquest of new spaces and new spectators began.

Ilkhom received many invitations from western festivals. We started playing in New York and Dublin, Oslo and Vienna, Copenhagen and Belgrade. We played in Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, the Netherlands, Italy, and Germany.

I have listed far from all countries and cities. Because it is better to talk about foreign tours in memoirs, sorting through the memory of a variety of topics and cases. Well, for example, what we felt when the wall between West and East collapsed and we, who never dared to dream of going to America, practically without knowledge of foreign languages, suddenly found ourselves alone with Western civilization, not with “our” viewer, but with a different lifestyle, with the necessity to merge into a different context.

I could have separately spoken about how and what has changed about my actors, who discovered the world for themselves, what they gained, and how, in my opinion, they lost a certain charm of idealism that was once inherent in us, wandering in the vast expanses. For, alas, not a single acquisition protects us from losses.

Over the past years, we have done many joint projects (far from always successful), student exchanges. We brought to Tashkent a huge number of foreign performances and performers. As a director, I directed a series of performances in the West.

We can say that Ilkhom turned out to be a kind of center of cultural exchange between eastern Tashkent and the West. In 1993, we even held a very ambitious festival called “EAST-WEST” (performances from more than 20 countries were shown). However, nothing has saved us from new trials and breaks in History.

In the early 1990s, Ilkhom looked like a small island, trying to restrain tension and gravitate continents diverging in different directions.

***

Once, on Christmas Eve, in the theater we came together with people representing new entrepreneurs. I delivered a solemn speech on the occasion, congratulated people on the New Year, wished to reach out to each other and begin our partnership. Suddenly, one of the participants replied: ‚ÄúWe all owe to Ilkhom.‚Äù During the years of totalitarianism we grew up with your performances, feeling in them a different way of looking at things. Maybe one of us gained our inner freedom thanks to Ilkhom …

We didn’t collect any special money either in this or in subsequent meetings. But the words were remembered, because they were not only beautiful, but said a lot about themselves. Moscow critic Nina Agisheva, who had been observing Ilkhom for a long time, once remarked: “Ilkhom having been born like this, could be born this way only in Tashkent, but modern Tashkent, as we know it, has become so because there is the Ilkhom Theater there.

Twenty-five years later, after we started our business, I will allow myself to agree with this idea: probably that’s the way it is. The story of Ilkhom continues. It is a living part of Tashkent, without which Tashkent is not Tashkent.